Gelsenkirchen

When I went to my grandmother’s house in Gelsenkirchen, I experienced an encounter similar to the one Deleuze describes when he says, “we first encounter the affect of a work of art.” But this time, there was no artwork in front of me.

As children in Antep, we used to look forward to the summer months with great anticipation—there was a whole ceremony around the arrival of our grandparents from Germany. A long time ago, when there was no airport in Antep, they had to fly to Adana first. From there, someone familiar—sometimes my father—would go and pick them up from the Adana airport. And we would wait for them to arrive. We would wait for the people from the other world to come. For some reason, they always arrived at night. Since I couldn’t usually stay awake that long, I would go to bed after asking my mother to wake us up. We would also tune our bodies to wake at the sound of the arriving people. And it was always our bodies that woke us.

Still half-asleep, we would hug the arriving guests, not quite understanding what was happening yet, but already moving around like curious cats, thrilled to enter the next most important part. Our tails—or so it felt—would always lean toward the suitcases. Somehow, we just wanted those suitcases to open, for the spoils of another world to scatter around. We waited for the scent of Germany to fill the house.

And those mattresses laid out everywhere—I’m not sure if we prepared them before their arrival or only after they arrived. But for some reason, after the suitcases, that’s always the next thing I remember. After a long and tiring journey, they would arrive at the house, and then the suitcases would be opened and spilled across the space. Some would be opened, some left untouched. The opened ones would fill the air with strange new smells. Amidst all this activity and ceremony, longing would be eased.

Like those fade-out moments we add while editing films, people would slowly spread out onto the mattresses laid on the floor, onto the couches, onto the fold-out beds. Even though everyone was awake, it was strange—at night, people would always speak in whispers. And among those whispers, with the sly grace of a cat who had secured the suitcases, I would drift off to sleep.

At the door step, I realized that the scent from that suitcase had filled my grandmother’s entire house, even without a single suitcase being opened. It was as if my grandmother’s house had been transformed into an 80m², two-bedroom, one-living-room version of an expanded 30-kilogram suitcase. The house was surrounded by that scent. And this time, my grandmother was inside the suitcase too. It was like a museum of smells and emotions. I think the first time I visited; it was just the two of us.

What fundamentally distinguished this museum from the museums of the state or of scientists was that its design and organization weren’t grounded in record-keeping, history, or science, but rather in an organization of affects. You could see that just by looking at the photographs scattered around. Though I don’t know if everyone who looked at them could see it. I did—because I couldn’t see myself in any of them. Or maybe the organization was such that I simply wasn’t in any of the photos my eyes touched. There were sons, grandsons/doughters, daughters-in-law, sons-in-law, daughters. I wasn’t there.

Later, the words that could explain the reason for my absence came from my grandmother’s lips—when I had come very close to death. But for now, I think I’ll cast my vote for not being too eager to wander around those rooms of affect labyrinth just yet.

At the time, I didn’t dwell too much on my absence there, thinking that my grandmother had always been a rather unpleasant person since her youth anyway. What intrigued me more was the idea of tracing the presence of these ghosts around the house. She only watched Turkish TV channels. While the news showed people’s misery and suffering, she would offer her own prayers in response. It was as if she had shut herself away in a temple, like a monk, praying to God for hours to keep such evils away from her family—and this sometimes became an incredible, and at times frightening, experience for me.

Because in those rooms of the labyrinth, the ones where I had come very close to death, she was present too—with her prayers. And when you’re forced to listen to your own prayer, it’s hard not to feel terror. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem so easy to avoid that.

You could see my grandmother sitting in any corner of the house, sometimes praying out loud, sometimes silently, seated on a chair or a couch placed somewhere in the room.

And sometimes, when this woman who prayed began to drift into an incomprehensible whisper, her prayers could turn into the murmurs of a Greek god casting curses from the heavens. The moments I listened most closely were the ones when I felt her whispers shifting from prayer to curse. Because after a while, I began to sense traces of this transition in her expressions, in the way she moved, in her swaying gestures. After all, when your prayers fail to punish the people you’re angry at, that anger eventually needs to leave your body somehow—and those compulsions begin to shape the rhythm of your eyes, your hands, your whole body.

In those moments, I would try to understand who she was cursing, what form and intensity those curses took, and in which direction—and for what reasons—they were aimed. That, for me, was one of the most fascinating games when it came to my grandmother.

In such moments—right at those points of transition—if one was alert, curious opportunities could scatter themselves around.

One day, I was wandering through a market in a village in France. It was strange day—during the day, there was a market in the town center. I was walking around. I passed through the bazaar. All of a sudden, I saw a woman who was selling things, and she was staring directly at me. Then she said, “Angels are passing by.” Then she wanted to give me something she was selling as a gift. It was hard to accept, but I took it.

Then I went and found a man selling flowers. I asked for a bucket, but he also gifted me a rose. I didn’t want to give the rose to the woman—as a way of keeping it polite, not intrusive.

I went back to the woman who had been staring at me. I gave her the bucket without saying anything. She was happy. Then I left with the rose. I wanted to sit on a bench next to the church. There was an old couple sitting there. When I sat down, the old lady saw the rose and smiled at me. Then I felt I had to give it to her. I gave her the rose. She thanked me—or so I assumed, as I didn’t know her language.

But when they left, she came up to me, bent down, and gave me a kiss on the cheek.

It was a marvelous day.

Then I remembered: that angel was Kairos, the god of opportune moments.

Just like that, my grandmother’s transitions—from love to hatred, from hatred to anger, from anger to curses—always carried the potential to carry something else along with them.

One day, she started speaking with love about some people I knew very closely. Perhaps in her words of love there was also an envy—maybe what she saw as abundant in them was something cocooned and lacking in herself. She was talking about my aunts. I overheard her say: “They’re like Snow White.”

That sentence was wrapped in such a peculiar affect that, instead of thinking she had said something nice about my aunts, I found myself overcome by the feeling that she was angry with them—precisely because of that.

“So white. So beautiful. Like Snow White.”

And right there, just after that…

Because they are Armenians!…

Even though there was plenty of physical space, it never felt like there was space for me. Sitting at that table carried a kind of emotional weight—as if the presence of those affect-people, invisible but insistent, filled the air between her and the rest of us. I found myself on the edge, both literally and figuratively, never quite able to enter that circle. It felt like the table belonged to them. And I was always just passing through.

In fact, as my grandmother grew very old, she began to soften toward me. As children, our emotional world is shaped by something primal—like the first humans, surrounded by elemental forces. Just as the sun once created all life for the earliest people, for me, the destroyers of all life were always the gazes of my grandmother and Nimet yenge. Their looks carried a divine power that could undo everything.

Since retreating into her own temple, those frightening gods had taken on another form. It began to seem to me as if they no longer looked outward at all. While I had once been seen and judged by my grandmother in ways I never wished to be, now I felt as if I had become invisible.

And if what she saw now was no longer me, I couldn’t help but wonder whether her gaze had turned inward—toward a final reckoning with those affect-images she had spent a lifetime breathing spirit into. Her eyes, once cast outward with authority, now seemed just as deeply turned inward.

So rather than a fear she might direct toward me, her presence now felt more like a confrontation—through whispers and curses—with the ghosts of a past she was still entangled with.

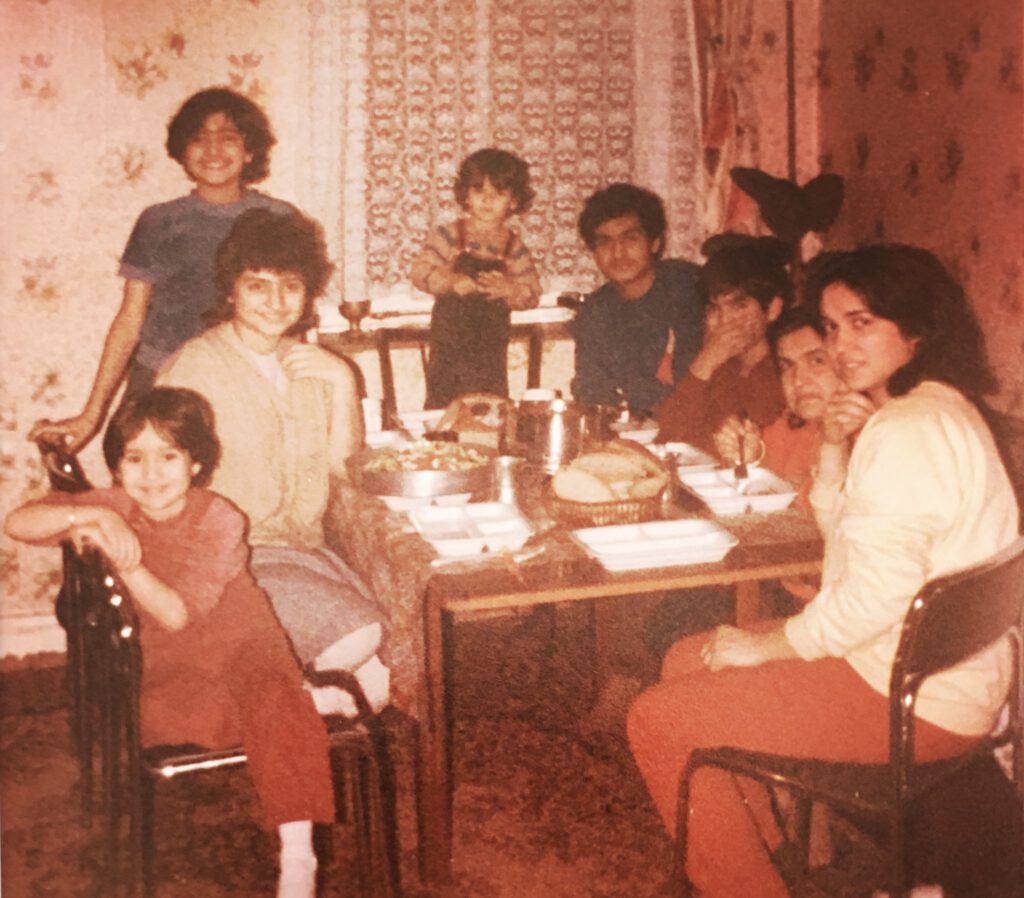

Gelsenkirchen early 80s.

And maybe—just maybe—my own ghosts of her could no longer see her either.

But my grandmother, like an essayist, was still roaming after her own ghosts.

Anyway, since my mother was always the family’s servant girl, the slave girl, I had automatically internalized the task of setting and clearing the table. So I would always gravitate toward the kitchen.

But that evening—the day my uncle arrived—my grandmother had the dining sets brought out from the closed cabinets in the living room. And that moment became even more interesting because it echoed a memory lodged deep in me.

A long time ago, I think during my first visit to Germany, my grandmother had opened that same cabinet. She reached in and, with the hand bearing a ring marked with the letter Z (I can’t remember if it was her right or left), she gently touched the plates. Then she closed the cabinet again.

That was it!

That’s how Benjamin’s aura was breathed into people’s everyday lives. There was no need for grand ceremonies, unreachable rituals, churches, or museums. Not even a god was necessary.

There was a vast rift between those plates and me.

And for my grandmother, perhaps not as painful—but still, a rift all the same, between her and those memories her gaze had once returned to.

And so, being a guest at the edge of that table felt exactly like being at the edge of everything—at the side of my mother’s family, at her childhood ice cream shop, at the duck pond, near the ice cream truck, and in Gelsenkirchen. Always at the edge of the table, where others built meaning and breathed spirit into their cherished objects—into their personal sacreds.

I always felt like a stranger, sitting just at the corner of those relationships, like someone who could slip off the edge of the table at any moment.

I kept telling myself: This couldn’t be the Gelsenkirchen my mother spoke of. This wasn’t it. It couldn’t be.

But when I tried to dress Gelsenkirchen in the world of thought, dreams, and imagination I had sewn together from the lullabies my mother whispered at my bedside, it didn’t even fit—not too big, not too small, just wrong.

Painfully wrong.

In those deepest chambers of my mind, the ones I had kept hidden from everyone since childhood—those corridors where I performed the rituals of happy days yet to come—time and space didn’t just creak. They cracked, tore apart.

And people, without even blinking, shattered it all with terrifying acts.

Yet, watching destruction can often bring a strange peace.

Transitions from order to disorder carry their own kind of calm. The tightly knotted ties that kept everything stuck begin to loosen. In those moments, even the skin and muscles that held those thoughts in place seem to breathe a little easier.

But perhaps the most important thing that happened to me here was this: I used to believe that my grandfather—and all these people—were superhuman, almost angelic beings. To me, they were supernatural.

Yet every time they came into contact with that room in my mind, I began to see something new in them. Because the structure I had built and stitched together was suddenly under attack—under siege by their hands wielding hammers, their bloodstained shirts, their tongues made of a thousand serpents.

They tore it apart.

They shattered it completely.

That was it. Exactly that.

I wasn’t unhappy watching the collapse of that structure.

But the ruins didn’t resolve anything—they scattered like absurd bullets, ricocheting into other rooms of my mind, lodging themselves in places they didn’t belong, cracking spaces that had nothing to do with it. Their actions didn’t just destroy—they fractured me further.

I had to face the reality that my beloved uncles were not kind-hearted men, that the aunts I believed were my mother’s flesh and blood were in fact entire systems of silent destruction, moving like the world’s most powerful intelligence agents.

I had to keep rewriting history—again and again—under merciless bombardment.

And as I tried to carry the walls I once loved, I was forced to be crushed beneath them.

We often think that traumas come from painful things—we look for them in sorrowful days, in memories that hurt.

But I think the deepest traumas are hidden within the moments we were happiest.

Because we pour so much force into those moments that, when they collapse, they release a kind of energy that can tear through the body, through emotion—just like how the most devastating explosions are born from the splitting of a single, simple, powerful bond.