Methodology

Ludwig Wittgenstein: ‘We think we are tracing the nature of the thing, but we are only tracing the frame through which we view it’ (1958)

This node traces the genealogy of my methodological formation: from an accidental encounter with a camera in Berlin, to apprenticeship with Thomas Balkenhol, to conversations with Babacan Taşdemir, and later to the writings of Richter, Farocki, and Adorno. These lived experiences form the roots of the methodology I later articulate in the thesis. The materials here (essays, videos, photographs, memories) show how theory and practice were never separate domains, but co-emergent in the process of inhabiting spaces, images, and relations.

In 2009, after a series of coincidences, I found myself spending half an hour in front of Filmuniversity. I had no prior intention of entering or any familiarity with filmmaking practices. I was simply there, waiting for someone as they took their exam. However, one thing that stood out to me was an overwhelming urge to possess a camera.

On the same day, I left Berlin and returned to the Netherlands where I was living as an Erasmus student. The program I was enrolled in there was completely different from the one I was studying at my home university in Ankara. It was an unfortunate mistake that led me to this program as none of the courses aligned with my home university’s curriculum. Faced with this mismatch, I decided to focus solely on taking German language courses.

Feeling out of place at my Erasmus university and burdened by the fear of financial consequences, I found solace in one aspect: working illegally to earn money and cover any potential penalties resulting from the discrepancy between my home and host university. In the upcoming chapters, I will delve into the details of how I found this job. Primarily, I worked for an individual who organized Turkish weddings. There was no specific job description, and I would work ten hours for a mere 50 Euros. My responsibilities mainly involved serving as a waiter and being a versatile handyman capable of performing various tasks.

With the money I saved from this work, I was able to purchase a camera and started capturing photographs. To my surprise, the pictures I took during my European adventures won a prize in a nationwide photo competition when I returned to Turkey.

Growing up in a socio-political context where cultural events such as going to the cinema, theatres, or concerts were not a part of my life. It was only when I started university that I began to explore these realms. It was in this context that a particular film I watched during my time in Germany had a profound impact on me. The film resonated deeply within me, as it depicted emotions, images, and relationships that were reminiscent of my own childhood. It was through these two encounters that my interest in filmmaking began to take root.

I.II. Audio Visual Research Center

The profound emotions stirred within me by that film, combined with the validation of winning the prize, led me to make a significant decision. I made the bold choice to leave everything behind in my life at that time. I stopped attending my courses in the program and defied the expectations of my family. Instead, I sought out the Audio-Visual Research Center of the university in Ankara. It was there that I had the privilege of meeting Thomas Balkenhol, a distinguished German film editor from Munich. Thomas had been actively working in Turkey for over forty years, making significant contributions to the local cinema through his involvement in numerous films.

I found myself spending all my free time alongside Thomas, immersing myself in his world. To many, he was seen as a peculiar character. Someone who struggled with conventional forms of communication as an instructor. However, I believed that language was just one of the tools we have to form connections, and Thomas had his own unique ways of fostering understanding.

Rather than relying solely on verbal communication, Thomas utilized different mediums to convey his thoughts and ideas. He engaged with us through the act of editing images, presenting films that we may not have discovered on our own. One particular favor he granted me was allowing me to be present in his office while he worked on editing projects. Sitting beside him, I had the privilege of observing his editing process, especially during his work on the film “Gelecek Uzun Sürer” (2011).

During those editing sessions, there was also Çiko, Thomas’s stray cat. Normally, Çiko would occupy the chair, attentively watching Thomas. But when I arrived, Çiko graciously relinquished the chair to me and made himself comfortable on a nearby pillow by the window. We all didn’t engage in verbal conversation, yet there were moments of shared understanding. Sometimes with Thomas, we would find ourselves laughing together, even though we might not have known the exact thoughts that prompted our amusement. As Thomas continued to edit, I absorbed invaluable lessons in editing simply by observing his work.

Over time, Thomas generously provided me with a designated space in the same room where he worked. He allowed me to embark on my own editing endeavours. I stumbled upon an old camera and began documenting the lives of gambling students at the time. Eventually, I edited my very first short film within the confines of that room. From that point on, Thomas started assigning me camera and editing jobs. We started collaborating with other directors. On one hand, I felt immense happiness being immersed in the world of filmmaking alongside Thomas. However, alongside that joy, there was also an undercurrent of an uncanny feeling that lingered within me.

The intriguing aspect was that I had no formal theoretical background in filmmaking practices. My education primarily involved learning through observation and hands-on experience. Nevertheless, I always had a deep appreciation for the films Thomas shared with me. When we embarked on a project with Greek director Efi, where we had the opportunity to shoot Greek and Turkish musicians and document their journeys within their respective spaces, everything seemed perfect. Yet, whenever I delved into my own personal projects, a complex mixture of emotions emerged while I was both shooting and editing.

The revelation of this intricate feeling first occurred to me during the time when I was capturing the illicit gambling habits of students. In Turkey, gambling is strictly prohibited, and it piqued my curiosity when I discovered that my roommate in the student dormitory was involved in such activities. Intrigued by the stories he shared, I mustered the courage to approach him one day and express my intention to create a film centered around this subject matter. To my surprise, he readily agreed and granted me permission to accompany him one night to the clandestine gambling venue.

Stepping into the gambling house was a moment of sheer astonishment for me. I had never anticipated such a well-organized setup orchestrated by students. It felt as though I had walked into a scene from a movie, with the house resembling a slice of Las Vegas. Engaging in conversation with the organizer, who was also a student, revealed the immense wealth he was accumulating—a fortune that seemed unimaginable for someone of our student status. The atmosphere was vibrant and lively, painting a picture of a colourful and exhilarating existence. What struck me even more was the realization that I personally knew half of the individuals involved in the gambling activities, as they were fellow students from my university.

Within the confines of that house, I captured footage, conducted interviews with the students, and immersed myself in their world. They openly shared their stories of how they started, their enjoyment of the experience, and even provided me with insider tips, such as strategies for reading people and the lucrative earnings they made. It almost felt as though I was crafting a promotional film, inadvertently enticing others to explore the realm of gambling within the university setting. One of them even remarked, “There is a sparkle in the eyes of those who gamble, and I see the same spark in your eyes.” I had collected ample material to portray this world authentically. Yet my intention transcended mere documentation. It was during the final interview that something profound occurred which left a profound impact on me.

I.II.I. Intimate Spaces

Our university campus encompassed not only academic buildings but also dormitories, where we resided. I was assigned a room on the top floor, among twenty-four other rooms, and over time, we all became acquainted with one another. The seniors took it upon themselves to guide us through the intricacies of university and dormitory life, ensuring a smooth transition for us. Together, we cooked meals, watched films, and engaged in various recreational activities during the evenings. I distinctly recall our collective involvement in a real-time web game, where every weekend we would convene, sharing laughter and discussing strategies. We even organized jogging sessions for newcomers, fostering a sense of camaraderie and support. It felt like a close-knit community, where we not only shared experiences but also learned from one another. Our dormitory was our collective home, a place where we forged relationships that felt like family.

However, after conducting my final interview with the senior student who was also a gambler, a profound realization dawned upon me. Despite spending four years together in the dormitory, considering it a home and developing friendships, I came to understand how little we truly knew about one another. It was a stark reminder of how little we share and how much remains concealed, even within what we perceive as our own family.

We met in his room; I had my camera prepared. I do not remember why but I decided to not to record video. It was in the middle of the night. It was dark in the room. I remember we had a very low light. For years, I tried to figure it out how it became such an intimate space where we both open ourselves to each other and talked for hours. It was totally different from the idea of interview that I learned. The things we share became so personal. The more we talked the more we opened ourselves up. That was not an interview. It was like a moment suspended in time as Chris Marker told in Sans Soleil.

A person came to life in front of me as conversation went, filled with blood and vitality. Our conversation went beyond gambling as he shared his personal experiences growing up, his thoughts on his studies, and his emotions. The raw honesty and vulnerability in his words revealed deeper insights into his motivations for gambling and his struggle with his current path in life. I gained a newfound understanding of his situation and the reasons behind his actions. I visited with the intention of capturing information to depict a specific world, however, the interview turned into a platform for the person being interviewed to open up and express their previously suppressed thoughts and feelings.

We both hailed from marginalized backgrounds, belonging to the subaltern class. As he recounted, there exists a segment of society for whom life is not shaped by the conventional notions of expectations, desires, or aspirations. Instead, their dreams remain intangible, confined to the realm of virtual spaces, unable to materialize into reality. These dreams serve as a refuge, a means to grapple with the unfairness of their circumstances, rather than concrete ambitions to be realized. They find themselves ensnared in a labyrinthine existence, akin to a hamster seeking an escape route from the confines of its maze. Their motivation stems not from a pursuit of future dreams, but rather from the profound fear of being trapped within the limitations of their present reality. While these individuals may not possess a clear understanding of what they truly desire, they are acutely aware of what they wish to avoid.

My original intention to document the gambling habits of students proved to be futile within the confines of that room. However, an unexpected turn of events occurred as I found myself engaged in a profound conversation resembling a therapeutic session. The person before me delved into his childhood, familial background, educational journey, and the intricate web that led him to the very point in life where he felt trapped within the labyrinth of gambling. His introspective and deeply personal reflections left a profound impact on me. In that moment, I experienced a shift in perspective. As Bakhtin suggests, language can only truly perceive itself when illuminated by the presence of another. That night, being in the presence of someone grappling with their own struggles allowed me to gain a deeper understanding of my own experiences. Each question he posed to himself resonated within me, and through his introspection, the intricate labyrinth in which I found myself became more visible and comprehensible.

Upon my departure, I found myself burdened with a multitude of questions. I sensed a connection between my aspirations in filmmaking and the escapism inherent in his approach to gambling. Yet, I hesitated to inquire further, feeling a certain shame associated with probing into the depths of his involvement. However, it became evident that there was a profound history and personal struggle intertwined within his story. This encounter left an indelible mark on my approach to film, prompting me to question my own intentions.

I wished that he possessed the camera and editing equipment to articulate his own narrative, but instead, he entrusted me with that responsibility. It weighed heavily upon me, as someone from a similar background and shared experiences had entrusted me with their story. It was in that moment that I resolved to undertake a similar endeavor to what had transpired in that room—a more intimate, reflective approach to filmmaking. I sought to shift the gaze inward, exploring the vulnerable and intimate world of personal narratives.

Years later, I came across the writings of Hans Richter, shared with me by Ersan, my second advisor for this thesis. Richter delineated a distinct film form that critiqued a specific style of documentary filmmaking, which he referred to as “postcard” documentaries. According to Richter, these documentaries presented a falsified idealization of reality, employing romanticized visuals and contrived characters. He argued against a mere chronological depiction of external phenomena in a quest for comprehensibility, as he believed it failed to capture the intricate complexities of life. Richter was more inclined towards exploring abstract concepts and the emotional undercurrents surrounding external phenomena, positing that postcard documentaries fell short in conveying these profound ideas.

During my collaboration with Thomas, I lacked the tools and knowledge to fully contemplate the significance of these experiences. However, this particular endeavor illuminated the necessity of adopting such a perspective. If I wanted film to transcend being a mere means of escapism and instead become a space and form that I actively shaped, it was imperative to embrace this approach. It was the only way for me to create something that I authentically chose, a vehicle through which I could engage in profound thinking, dream freely, and bring those dreams to fruition. This realization underscored the importance of developing a personal and reflective framework within my filmmaking journey.

I.II. II. A Wise Man

I continued my work alongside Thomas in the room, arriving early on some days to feed Çiko and settle down at the desk that Thomas had arranged for me. Thomas, on the other hand, would make his way to the room by walking. He was often taking the opportunity to explore his surroundings and gather flowers along the way. It was through his influence that I learned to appreciate the presence of flowers in my workspace, bringing a touch of nature and beauty into the creative process. After some time, a new individual entered the room who added a different dynamic to our working environment.

As this new individual started coming regularly to the room and occupying his own desk, it became apparent that he had a striking contrast to Thomas. In the beginning, our interactions were minimal, with our desks situated next to each other. I would diligently work on my images while he engaged in his own activities. Initially, we didn’t exchange many words, but our desks were placed next to each other, allowing me to observe his habits.

His desk resembled a miniature library, filled with an array of books that seemed to define his workspace. It was difficult to discern whether the books were merely objects placed on the desk or if they were integral to its very existence. Whenever he arrived, he would immerse himself in reading, as if being pulled into the depths of the books, and occasionally, he would pause to jot down his own thoughts and reflections.

At a certain juncture, it seemed that I had piqued this man’s interest, and he began engaging me in conversation. He was the antithesis of Thomas, a man of abundant words. He delved into books that had never been a part of my life. In my family, storytelling was the primary source of knowledge and imagination, and the idea of someone reading extensively was foreign to me. I had only encountered books during my university studies, and they were not ingrained in my upbringing.

This man, however, embodied a walking library. His wisdom emanated from him, and I found myself captivated by his every word. I listened intently, almost entranced, as he shared his knowledge and insights with me. It was a fascinating and enriching experience to be in the presence of someone so well-versed in literature and ideas.

In the midst of our conversations, I found myself consumed by a burning desire to learn more, to delve deeper into my own struggles and pose seemingly naive questions. Babacan Taşdemir, with remarkable patience, would expound upon theories, ideas, and philosophers that were entirely foreign to me. It was like being drawn into a black hole of knowledge and understanding. Editing films took a backseat to my overwhelming thirst for wisdom and insight, which I quenched through our discussions.

Babacan was in the process of working on his PhD thesis at the time, and he generously shared his expertise with me. He would explain media theories, discuss film history, and introduce me to a plethora of names and ideas that I struggled to retain in my memory. McLuhan, Marx, Horkheimer, Adorno, Barthes, Althusser—these were just a few of the many names that would resurface in our conversations.

During that period, comprehending the ideas and philosophies of these thinkers was a challenge for me. Nonetheless, one thing became clear: I needed to delve deeper into the intellectual realm that Babacan came from. It appeared that in that world, I could discover the tools to contemplate and analyze under the guidance of these renowned philosophers. I am immensely grateful to Babacan for his invaluable influence on my journey. In the words of Rumi, “Not only the thirsty seek the water, the water as well seeks the thirster.” I was seeking a path, and Babacan appeared to guide me towards the Media and Cultural Studies program, where the seeds of this thesis began to flourish.

I.III. Another Space-time, another language and thinking

Out of the numerous applications to the program, only around thirteen students were accepted, and I was fortunate enough to be one of them. As I transitioned into this new cultural space, I also encountered a shift in the language space. While the formal language of instruction was English, the discussions in class were predominantly conducted in Turkish. However, this Turkish language was distinctively different from what I was accustomed to. The sentence structures, choice of verbs, and the conceptual framework used by professors and fellow students were unfamiliar to me.

In my first seminar course, titled “Economy Politics of Media,” taught by Assoc. Prof. Dr. Barış Çakmur, I received an email from him with the subject line “Read.” The email was filled with writings, particularly by Karl Marx. Marx’s words resonated with me deeply as he discussed the experiences of people I grew up with, including my own. Since the age of eight, I had been working in some capacity, but I had never come across such descriptions in my life. While I was familiar with the people and the working culture, these identifications Marx presented were entirely new to me.

As I immersed myself in the language used by my professors and fellow students, I realized that my world of thoughts was undergoing a significant transformation. It was a challenging process, but I patiently listened, observed, and attempted to understand and emulate their use of language. It felt like a profound shift was taking place within me. I began to notice that when you change the linguistic space you inhabit, your thinking patterns and actions also undergo a change. I was evolving into a different person, and with each passing day, I was finding my way within this new linguistic realm.

In the midst of my studies, I found myself surrounded by fellow students who had received a solid education and were actively involved in political activities. They were members of political organizations and passionately engaged in political protests, including the Gezi protests that swept across the country during that year. It was a transformative experience for me as it marked my first engagement with street politics. In the streets, we fought against the police with a sense of organization and determination that felt like being in a war zone. It was a stark contrast to the language space I had come from, where such actions would have been deemed as terrorism. But here, we fought for freedom, justice, equality, and against what we perceived as the oppressive rule of Erdogan. In our anonymity, we even created propaganda videos with friends, urging people to join us on the streets and be part of the movement.

Later, people also produced numerous videos prior to the referendum for the change in the governing system of Turkey. However, there was an unsettling realization that these videos had little impact on the supporters of the opposing side. It didn’t require extensive research for me to understand this, as my own family and childhood friends were supporters of Erdogan. I witnessed first-hand the lack of engagement with these videos. Despite our aim to bring about change, it felt disheartening that our videos were primarily consumed within our own cultural and language space, unable to transcend the boundaries that divided us.

When I attempted to share videos made by people opposing Erdogan with individuals who supported him, I noticed a strong resistance and refusal to watch them. It was as if they reacted with hostility, rejecting the videos almost instinctively. It reminded me of how the body’s immune system reacts to a foreign object, mobilizing to eliminate it and protect the body. The videos challenged their existing beliefs and loyalties, triggering a defensive response. It became clear that these videos were unable to cross the boundaries and reach those who held opposing political views.

The impact of videos in political activism became evident when a video shot by a truck driver, who appeared to be a supporter of the nationalist movement party, garnered significant attention. This video led to the driver losing his job. This incident made me reflect on the power of language and signs. It seemed that the left-wing culture’s way of perceiving the world and engaging in politics was lacking something in terms of the language and signs they used. It seemed to me that they were engaging with politics in an aesthetic manner, observing workers, poverty, and inequality through a set of notions borrowed from Western philosophy. However, there was always something missing in their understanding. In the case of the truck driver, his way of speaking, his perspective on politics, and the language he used resonated strongly with Erdogan supporters. They were able to relate to his message, and as a result, they watched the video and began to criticize Erdogan. It had an impact that our previous efforts had not achieved. Perhaps this was why he faced consequences such as losing his job and facing oppression from those in power. The familiarity of his message allowed it to penetrate and affect those who shared the same cultural and linguistic space, challenging their existing beliefs and prompting critical thinking.

Initially, I sought to build something within this apparatus, but in the end, I found myself with more questions than answers. The loss in the referendum led me to question whether the working class had failed left-wing or if left-wing politics had already failed to truly see them.

I.III.I. Glasses and Objectives

In an interview, Harun Farocki described his relationship to Theodor Adorno, stating that Adorno was an important teacher and even a father figure for those who experienced West Germany in 1968. Despite this, Farocki acknowledged that they had to contradict and dissociate themselves from Adorno because he did not believe in the possibility of a revolution.

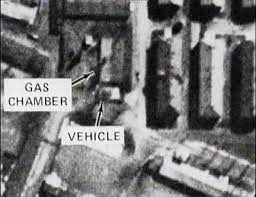

I wanted to address Farocki’s perspective because his statement in the interview and his film “The Images of the World and the Inscription of War” made me think differently. In the film, Farocki follows in Adorno’s footsteps by problematizing the concept of ‘Aufklärung’ (enlightenment) and its gaze in the production of knowledge.

“The Images of the World and the Inscription of War” starts with a simple description of the term ‘Aufklärung’ and expands upon it by exploring the ideas of measurement and the gaze of enlightenment throughout history. Farocki examines how knowledge production and visual representation have been influenced by these concepts.

At one point in the film, Farocki discusses how the Allied Forces studied war images during World War II. Not only were planes bombing targets, but they were also taking photos during these bombings. These images captured by planes were studied to analyse the field and develop new strategies for achieving victory.

Ludwig Wittgenstein writes, ‘We think we are tracing the nature of the thing, but we are only tracing the frame through which we view it’ (1958). Nora Alter, in her text titled “The Political Im/perceptible in the Essay Film: Farocki’s ‘Images of the World and the Inscription of War’,” analyzes the methodological approach and limitations of perception in Farocki’s film. By presenting this historical example, Farocki raises questions about the dynamics inherent in the act of viewing and analyzing images. The film suggests that the interpreters’ analytical framework, which primarily focused on identifying industrial and military targets, hindered their ability to perceive and comprehend the true nature of the atrocities committed by the Nazis. It highlights the constraints of perception and how certain aspects of reality can be obscured or disregarded due to preconceived notions, biases, or methodologies.

I came to know Adorno during my master’s program, and I was immediately captivated by his thoughts. I remember reading discussions in a work titled ‘Towards a New Manifesto for a Radical Politics’ by Adorno and Horkheimer. They delved into the transformation of universities, which had shifted their focus towards technical production rather than fostering critical ideas and approaches. Adorno and Horkheimer expressed the need for an alternative space where they could engage in independent thinking, productive work, and challenge the very foundations of the university system.

I have never had such a strong opposition to these structures, and I deeply admire the work that has been done within them. My only minor objection stems from the institutionalization of a particular gaze, which I feel can limit its capacity to encompass diverse perspectives. This objection is rooted in my personal experiences and my dual status between different social groups.

The program I was a part of had a vibrant culture, with every member being enthusiastic and passionate about their research. These projects shed light on various aspects of society, including ongoing events, historical occurrences, and the struggles of individuals. However, I couldn’t help but feel that the program itself had a specific way of viewing the world, and its students tended to employ the program’s theories and objectives to analyze and interpret politics, social life, and culture.

From my perspective, there was a noticeable difference in how I learned from my professors and engaged in discussions with my colleagues compared to the dynamics I observed when visiting my hometown and interacting with my family and friends in neighbourhood. While the researchers and scholars in my program had coined certain concepts and tendencies, I often struggled to effectively convey these ideas to my family using the language and knowledge acquired at university. Despite my efforts to share videos, support political movements, and articulate my thoughts with university-informed knowledge, I encountered little response or understanding from those who were studied.

Indeed, my efforts to bridge the divide between these two spaces often resulted in further polarization, ultimately leading to my estrangement from both my family and the academic community. My family accused me of adopting the language and mindset of those I had studied together, while disregarding the realities they believed in. Conversely, within the university setting, I didn’t quite fit the mold of a conventional academic. Instead, I was seen as an artist grappling with my own artistic ideas. This constant mediation between these distinct spheres prompted me to question whether there might be something missing or overlooked within the objectives and theories we employed within the university context, much like the contemplation expressed by Harun Farocki in his work.

In one of the projects, I worked on, I created a fictional character and documented my observations and reflections on him based on my university experiences. To further explore this character’s story, I decided to make a short film. There was a particular scene in the film where the character attends a performance by a dancer. The dancer performs in her living room, while people gather on the street to watch her through the window. The interesting aspect of this scene was that the spectators couldn’t hear the music accompanying the dance; they could only observe the movements.

After watching this scene, a colleague shared a quote with me that resonated with the idea of rhythm and perception. The quote, attributed to Gustav Mahler, suggested that if you watch a dance from a distance, without being able to hear the music, the swirling and twirling movements of the dancers may appear meaningless, as the key to understanding lies in capturing the rhythm.

Indeed, everyday life is filled with various rhythms and flows that shape our experiences and interactions. While certain rhythms may be more apparent and observable, there are often subtler and less quantifiable flows at play as well. These less measurable rhythms can have a profound impact on how people feel and behave within a given space. They may influence emotions, moods, and even the collective atmosphere of a place.

By solely focusing on the dominant rhythms and relying on the tools and frameworks provided by theories, we may overlook or undervalue the significance of these other flows. These alternative rhythms, which are not easily captured or communicated through traditional objective measurements, hold the potential to offer unique insights into human experiences and social dynamics.

By acknowledging and exploring these subtler rhythms and flows, we can gain a deeper understanding of the complexities of everyday life and the diverse ways in which people navigate and make meaning of their environments. It opens up avenues for considering alternative perspectives and approaches that go beyond the conventional frameworks provided by established theories.

Traditional academia, in its conventional sense, failed to provide me with the opportunity to explore and discuss the time and space in which I grew up, particularly in relation to the unspoken, ineffable experiences, feelings, dreams, and fears that shape our lives. I believe that these intangible aspects are integral rhythms within a space, influencing both our actions and the meaning we attribute to them. However, within the confines of traditional academia, there was limited room for engaging with and understanding these crucial dimensions.

I.III. II. Are you a filmmaker or a scholar?

Just before embarking on my master’s thesis, there was a tense meeting at my faculty, at least from my perspective. This program was initially established by members of the political science department with the aim of fostering collaboration with the university’s Audio-Visual Research Center. However, over time, the connection between the two institutions had waned. As a result, most students were primarily engaged in traditional research practices. Unfortunately, there was no one in the program who possessed expertise in both filmmaking and scientific research to provide guidance to someone like me. Additionally, there was no established protocol for evaluating a thesis that incorporated a film.

During this meeting, I was summoned by the professors and entered the room, feeling a sense of anticipation. They gestured for me to take a seat and then posed a fundamental question: “What do you envision for your future? Are you an artist, a scholar, or a filmmaker?” For me, the answer was straightforward: “I aspire to exist at the intersection of art and science.” This experience marked a significant shift for me, as it was the first time, I consciously articulated my desires and aspirations instead of searching for an escape route.

Time to decide

With all of these experiences, I have gained insights into my position in academia and within my social circles, as well as my intentions with the camera and film. Filming people and their sufferings posed a challenge for me because I struggled with the notion of reciprocating their experiences. It became one of my primary ethical principles when engaging in filmmaking. I didn’t want to feel like I was betraying the individuals from the spaces I grew up in. This concern is influenced by Adorno’s ideas. Film in a way was grasping a perspective of a world that we point out the camera.

During my time working at an industrial site in Gaziantep, there were also Syrians working in the site. My role was more focused on tasks such as sweeping animal waste out of containers and foaming up trucks. During this period, I had the opportunity to collaborate and interact with them. Over the course of three months, we developed a sense of intimacy and connection. They generously shared their stories and experiences with me, allowing me to gain valuable insights and knowledge from their perspectives.

One of them was from Aleppo and he shared his deep affection for Beirut, describing it as a beautiful place where he worked for some time and a place he longed to return to. It was challenging for me to ask probing questions in situations where individuals had lost their homes and dreams. He went on to share his experience of visiting the shores of the Aegean Sea. He spent some time observing the sea before deciding against crossing the border, ultimately returning to Gaziantep with his family. I felt unable to delve deeper into the subject. He mentioned that being in Gaziantep offered a certain degree of familiarity, a feeling that was at least reminiscent of home.

Finding the right words to capture the feeling is a challenge for me. A sense of shame enveloped me as I recounted my own circumstances. I was working there to support my father and awaiting my visa—a position of privilege. In that moment, I couldn’t bring myself to direct a camera at them or inquire further. They had entrusted me with their stories, sharing their experiences, and now I am searching for a way to convey it all through my own experiences.

One particularly profound experience took place in the very location of my birth. Our homes, interconnected like cells in a tissue, formed a unique tapestry of familial bonds. It began with my mother’s grand family, who built the central house, while their children constructed their own spaces around it. This intricate arrangement resembled the core of a labyrinth, with each subsequent dwelling becoming a new corridor. It was within one of these halls that I came into existence, and throughout my life, I have traversed the various pathways woven by my ancestors.

During my visit to the ancestral home after the war in Syria, I found myself contemplating the idea of venturing into the grand family’s section of the house. Memories of this space, which I will delve into later, flooded my mind. Looking at it from the outside, it appeared deserted, and a sense of sadness washed over me as I realized that people had left the house. I entertained the thought of exploring and fixing certain areas that may have fallen into disrepair.

In the evening, as darkness settled in, I made my way through the hallway. These hallways typically consisted of one or two-room houses positioned near the main road, connected to one another by a narrow passageway known as the “dehliz.” There was a solitary light fixture in this hallway, meant to illuminate the path. However, as a child, I would often inadvertently break the bulb while playing, leaving the corridor engulfed in darkness. Even now, the fear I felt in that dimly lit, broken hallway resurfaced, reminding me of the unease it once evoked in me.

As I walked through the hallway, I noticed that the light was once again not functioning. Instantly, the familiar fear from my childhood resurfaced, and as an adult, I hurriedly made my way towards the door of the house, seeking refuge from the darkness. To my surprise, the door to the main house, the center of the labyrinth, was opened briefly before being swiftly closed again upon noticing my presence. Throughout the day, I had believed that no one was there, as there were no sounds or signs of anyone’s existence.

Entering our side of the home, I spoke to my mother about what had transpired. She informed me that there was a family hiding in the grand family’s section of the house, having fled from Syria. They were fearful of being seen and only interacted with my mother. The father would leave the house solely for work. It dawned on me that the darkness, which had instilled fear in me, served as a sanctuary for others. I realized that children were venturing out of the house under the cover of darkness, and life was unfolding within the confines of the evening. I knew I would incorporate this experience into my thesis, but capturing it on film proved to be a complex dilemma. The echoes of a film reverberated in my mind, adding to the complexity of the situation.

“-You saw nothing in Hiroshima.

Nothing.

-I saw everything, I saw the hospital– I’m sure of it.

The hospital in Hiroshima exists.

How could I not have seen it?

-You didn’t see the hospital in Hiroshima.

You saw nothing in Hiroshima”