Living Room

I still find it strange that this room ended up being titled “living room.” To define it so definitively feels like a form of erasure—an attempt to simplify what happens there, to render its ambiguities inert. For outsiders, it was the space where we sat and talked, drank tea—sometimes coffee. In the summer, it was always soda beside. I’ve often thought: in a life surrounded by so many unhealthy things, one needs at least one gesture that feels psychologically restorative. Soda was ours.

This, I think now, is the ritual logic of the devout wicked—those small offerings to the body meant not so much for health, but for conscience. A symbolic donation. A form of spiritual accounting.

To me, soda—like fasting—was never really about the body. It felt more like the residue of countless wrongs, a compensatory gesture rather than a path to transcendence. It never struck me as spiritual elevation, but rather as a form of vanity. A residue of guilt cloaked as discipline.

There’s a particular kind of moment: when someone sits so still, so absent of movement or sound, that we instinctively draw closer, just to feel if they’re still breathing. Not because they’ve collapsed, but because their stillness unnerves us. It’s as if, beneath the surface of ordinary calm, something is not quite right. These gestures toward health—soda, fasting, abstinence—carry the same energy. They are moments when we lean toward ourselves, quietly checking if there’s still something breathing within us.

To sense the breath of something good, even if faint. A bottle of soda, a day of fasting, a coin given to a beggar. Not acts of solidarity, but of self-preservation. Not care, but arrogance dressed in virtue.

Anyway, this is really what I want to say before losing my thread.

For an outsider, yes—this room is the living room. But in truth, it is a modular room. Its form shifts with time, adapting to different needs, different hours. At night, for instance, it becomes a bedroom—simple as that.

But its transformations go deeper. Because of its built-in closets, it also becomes a space of concealment. A zone of protection. As a child, I imagined those closets shielding my small body from Saddam’s bombs. Later, they became hiding spaces against the threat of being taken by the state for military service. The funny thing was that bombs that of Saddam was imaginary. there were only one side bombing.

The closets, the folds of this room, held not just clothes but the possibility of vanishing—of being safe by becoming invisible.

It is the first place I remember.

Or at least, I’ve always believed it was.

But now, as I revisit these memories in writing, I begin to wonder:

perhaps I’ve been lying to myself.

Perhaps the first place I truly remember was not this room at all,

but the hallway just beyond it—the passage that led elsewhere.

A corridor, not a chamber.

A threshold, not an interior.

And if that’s the case, then everything I’ve built on this memory—this room as origin—shifts. Not disappears, but trembles slightly. As if the foundations of remembering are not stable ground, but something more like mist, more like metaphor.

Lately I’ve been thinking: the new prisons of capitalism are no longer made of iron or stone. They are made of dreams. These dream-worlds—the ones we’re taught to believe in—have become our newest cells, our most intimate chains.And the most terrifying of all is the fear they quietly implant in us: the fear of dying without ever having become something.Never before, I think, has the human being attributed so much power to itself. Never has it placed itself so firmly at the center of the universe. But when that imagined world—where the self is powerful, exceptional, destined—begins to crack, the horror sets in.The moment one realizes that the dream of becoming someone may never materialize. That it was perhaps never real to begin with.That’s when the terror arrives. This is the new human:

the human who must be important. And what drives them to the psychologist’s office is not, ultimately, their mother, their father, or even their childhood. It is the unbearable possibility of being nothing.

Anyway, I feel myself getting lost again. This, too, teaches me something—how the doors of a labyrinth can suddenly open into an entirely different room. I realize once more that what overlapped in Nostalghia were not simply layers of time or crystalline images; they were affective forces. Not thoughts, not representations, but sensations—fields of intensity that pull the body without explanation. The hand reaching out in that film wasn’t reaching for something thinkable, but for something felt, something sensed beyond cognition. This is the domain of aisthēsis—aesthetic experience in its deepest, pre-cognitive register. If we were to add a fifth force to the four fundamental forces of physics, it would be affect: that invisible yet overwhelming energy capable of holding everything together inside a single, fragile universe. Perhaps that’s why it feels so powerful—because it carries the weight of what cannot be seen, only endured.

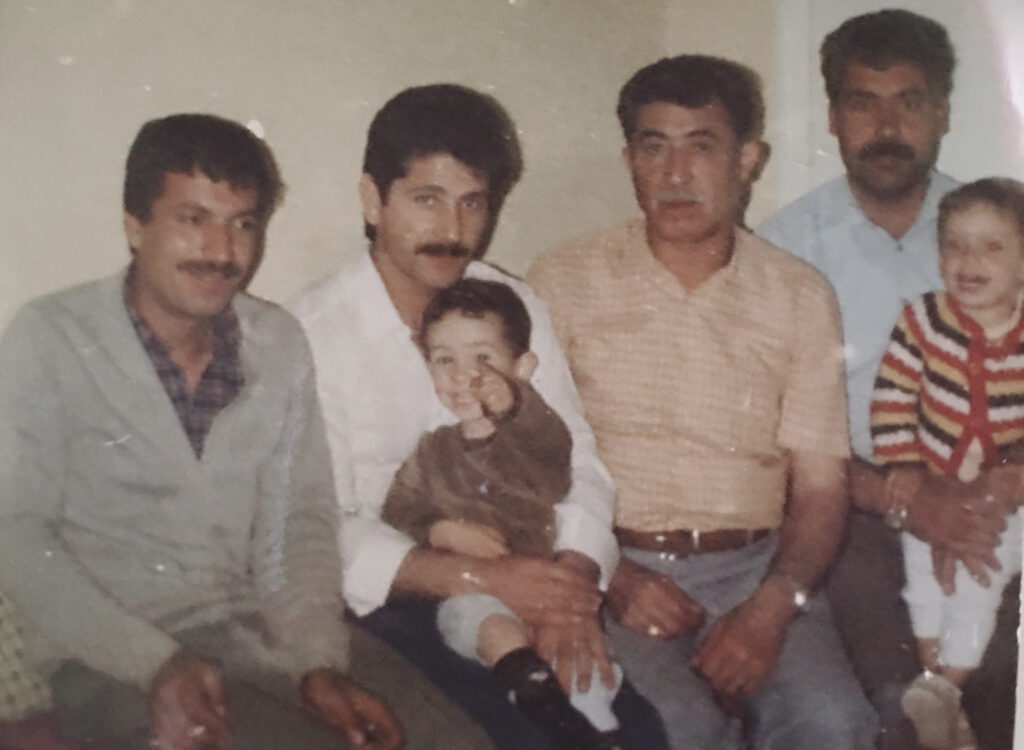

I remember hearing that the Gulf War was the first war to be watched on television—something I must have picked up during my school years. Another fragment: as a child, I used to hide inside the closets. These are memories I recall only vaguely, like mist that’s been passed down and half-claimed. Perhaps this is one of the first memories I can confirm because others have told it too. But this room—that room—was that kind of room. Maybe the reason I kept returning to that house, even as an adult, was the belief, or the feeling, that certain anxieties would ease there, that their origin might be found and undone at its source. Because the first televised war coincided with my childhood, and because the war entered our lives through the television, through analyses and speculations and grainy maps, I came to understand—through others, through words—that my house, my small world, was within range of Saddam’s missiles. And maybe that’s why I return to this part of the labyrinth—not because it is my home, but because every time I am pierced by the sudden memory of those missiles, I feel this is the only place that knows how to receive it. The closets were my temples, the sanctuaries where my inscriptions—my silent stories—could live. They waited there to hold me, to wrap around me like arms. Or perhaps it is me, now, still longing to curl inside them, to breathe in their shelter once more.

Of course, I’m not the only one who seeks refuge here. Every year, as spring approaches—

Strange, isn’t it? We feel that something in our lives is about to change. We sense it before we know it.

And here, too, something always changes. Sharply.

The birds arrive—the doves, in pairs.

They perch on the same iron rods, suspended for years above the strange concrete of the balcony.

They chatter incessantly—vır vır vır vır vır—talking to each other, annoying my mother as they make their decision.

I wonder: was it the same birds every year? Or their children?

And then there’s my mother’s anger.

It’s strange with us—we never say what we mean.

The preferences are clear. The birds’ intentions are obvious. My mother knows exactly what will follow.

And yet, for some reason, she scolds them angrily: “Go away!”

I never understood why.

She knows with certainty that they will build a nest, lay eggs, and stay there.

The birds know she doesn’t want them.

And still, year after year, it all plays out again—the arguments, the tension.

Eventually, the mother bird sits on one side of the eggs, and my mother on the other.

One of the chicks always ends up sick, and my mother saves it.

It’s a relationship that always ends happily.

But we’ve grown used to the idea that love must begin in sorrow.

Perhaps this, too, is about cultivation—like fertilizing the soil to yield the richest harvest.

We know something joyful will come.

And to make that joy stronger, we greet it first with anxiety, unhappiness, and irritation.

Everything that fears us in daylight falls asleep snoring beside us at night.,

When our living room turned into a bedroom at night, my mother would sometimes join us. The stories of how she came into the room have already been told—I hope you’ll visit those parts elsewhere. My mother was a curious character. The same woman who chased away the birds was, in truth, more foreign than the birds themselves. At night, she spoke a different language. She would come to bed and tell us stories. Sometimes they were familiar tales, sometimes I couldn’t follow them, because even her childhood memories felt like fairy tales to me. I had imagined the sound of the ice cream vendor from her childhood, the school she attended, the milk bottle she carried, and that sugar cone handed to her on her first day of school—those were all images of fantasy, illusions from a world that, within the spatial reality we inhabited, could only exist as fiction. Maybe that’s why, even when my mother wasn’t there, I would press my head between the wall and the bed and project dreams into that gap. Spazieren Gedanken. Every night, my mother took us traveling—from land to land, like a magician, like a weaver, like a spider spinning worlds. These worlds were sometimes the one she came from, sometimes a second dream world she had encountered while in that world. She would sing lullabies in another language. German was the language spoken in our house at night. My mother sometimes used German during the day as well. I didn’t speak German, but I always understood what she meant. And I would do as she said. It’s a strange thing—to understand a language without knowing it.

There’s a different kind of emotional texture I feel toward the women I remember only in fragments. It’s not just nostalgia, and not quite longing either—something subtler, a tenderness that feels unique to them. I often speak of love, of course, but the way they seemed to feel—more original, more singular—makes me wonder. Am I projecting this gaze onto them because my earliest memories of my mother, and of the house I was born into, are themselves so fragmented? Is it this broken, scattered quality that makes them feel so familiar? Have I inherited this form of perception—a way of seeing that is always partial, always reaching? Or is this simply what it means to look at someone with love: to see them always as incomplete, not because something is missing, but because they remain open—unfinished, like a memory?

How strange it is that the memories of others can become the first cocoon through which we relate to people. My mother’s stories were so beautiful. As I often say, children are like the first humans—we’re so close to them in our ways of thinking. The stories she told about Germany felt to me like myths from a realm of gods, peopled with superior beings and extraordinary objects. Her ice cream, for instance—the one she ate as a child—she described so vividly that I could already imagine the sound of the ice cream cart long before I had ever heard it. Hansel and Gretel, the lullabies—Hänschen klein geht allein—Germany, through my mother’s eyes, was always an enchanted world. And now, thirty years later, here I am, sitting in the country she once mythologized. But the strange part is that the entire meaning of Gelsenkirchen collapsed into my grandfather’s storage room, where my uncles, aunts, and grandmother seemed to have constructed a kind of inferno—like something out of a Hieronymus Bosch painting. Within a week, they had shown me that my mother’s Gelsenkirchen never existed. I even came to understand what it must have felt like for her to flee—not only that place, but the people within it—leaving even her child behind. Because I too ran, without looking back. Berlin and Mecklenburg were different, though. There, I could still dress my everyday life in fragments of the stories my mother used to tell at night. But like in Hansel and Gretel, these stories began to generate their own dangers. The issue wasn’t the gap between fantasy and reality—but that I was encountering, for the first time, the very forms I had once loved and been enchanted by in my mother’s tales. I was trying to clothe reality in the tenderness of her gaze, in the warmth of her storytelling. And that blinded me. It kept me from seeing how fascism had already taken root next to me, feeding on me like a vampire. The suffering I endured in Berlin seemed normal—because of my own foolishness. I believed that someone who brought me ice cream loved me, that a housemate was taking me on a journey through the magical worlds my mother once described. But he was a fascist. He was using me. While I thought I was living inside a fragment of my mother’s paradise, I was in fact being consumed by it. And to see that—I had to come to the edge of death.

This is what other people’s dreams are like too, I suppose. How is it that someone else’s memories or dreams can produce an affect in me? That sound of the ice cream cart—how strange it is. Something I’ve never experienced myself somehow took hold of me, especially after I arrived in Germany. Like magnets, strange fragments that don’t belong to me are drawn together and form something that feels like my own experience. I don’t know what exactly separates thoughts from memories—or memories from recollections, or recollections from affect—but I often ask myself: do these things, like cities, also have their own gaps, undefined spaces, places one might escape into? Maybe that’s why I’m drawn to empty spaces. Walking along the shore might be something like that. I think that’s why I came here. But today, something strange happened—funny, maybe, or maybe not—but definitely strange. I’ve been here almost three weeks, walking the same route nearly every day: down to the beach, following a path that splits and rejoins, but always passing the same familiar points. And today, for the first time, I saw something I’d never noticed before. I stopped—probably because a dog barked—and when I turned my head and looked around, I realized I was standing next to an old amusement park. Not even that old, actually—just one that only opens in the summer. But in winter, I never imagined it would look this ruined. It was like a broken memory. Everything I saw today was scattered across the ground: a headless figure still standing, a leg without a body, a sword next to a crown, princesses torn apart, warriors collapsed onto each other. Something was always missing. Objects were merged with other objects—cars placed around coffee cups, the wrong things inside the right forms. It was surreal. And I thought: this is exactly what memory is like. No image ever stays intact. Heads are replaced, limbs are lost, things pile up on top of each other. And yet, they keep chasing us. They never fully leave. They linger, they rearrange, they combine with other things—but they remain around us. These are the traces we leave behind. Or maybe they’re our ghosts.