Power of the False

Whenever I return to Antep, I encounter something I do not find ethically meaningful, yet it has become collectively functional. Everyone knows it, but no one names it, as if there were a secret pact. I cannot simply call it a “lie,” but yes, technically it is the act of lying — this shared notion, this common mechanism. A constitutive element right at the center of social processes and relations.

(Plato already gave politics its “noble lie.” Augustine condemned lying as sin but the church itself was built on fictions. Machiavelli, more honest, turned it into statecraft; Hobbes folded it into the Leviathan; Spinoza treated it as a law. And Nietzsche, of course, whispered that every truth is only a lie long forgotten. So why should Antep be any different?)

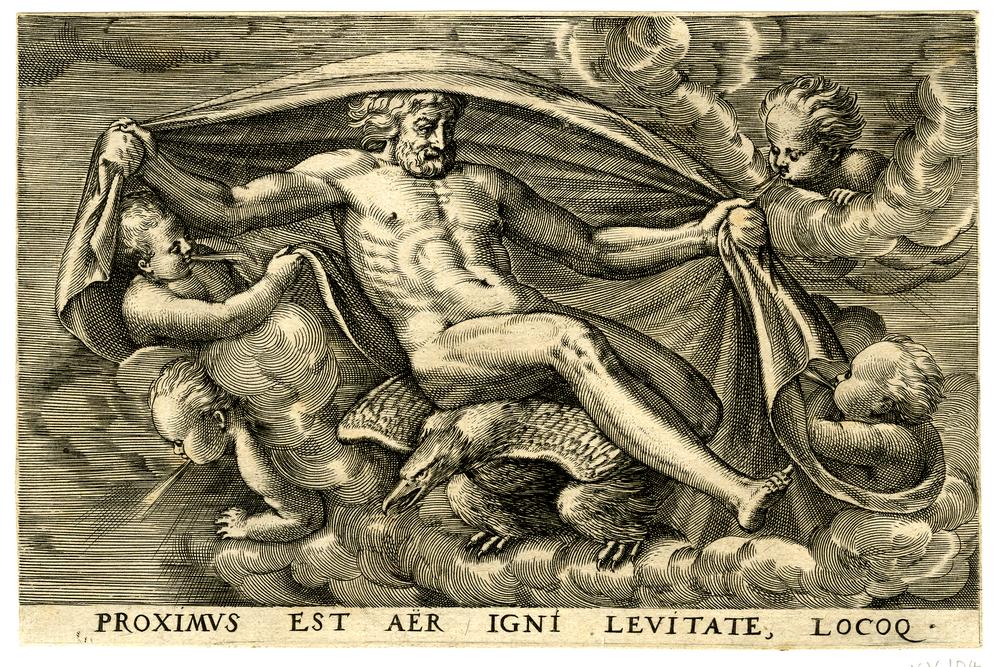

My father worked with Selim — despite me, despite all my pleading. Selim, the idiot. To call him a swindler is true, but it misses the deeper point: Selim possessed a trick. His power was like that of cherubs carrying God’s breath, his words rippling outward, leaving waves of affect in my father’s world. When he came to handle the work on the house we were building in the village, I thought I had met a con artist. But the con artist also recognized me; while I was away, he blew God’s breath into my father’s ear. Simple as that.

Selim is no innocent putto. He wears the mask of a cherub, blowing divine breath, but behind it he is a trickster, a conjurer. For my father, a believer in the world of false truths, Selim’s voice entered like a spell whispered into the ear — building villas out of dust, turning broken cars into symbols of status, wrapping every failure in the aura of a miracle. His voice was not innocent; it was enchanting, priestly, a counterfeit sacredness.

(There are such people who, sadly, might have become academics but instead became frauds. I remember once at Gorki, an academic stood up and introduced himself as one of the greatest liars, swindlers, and gossips among us intellectuals. He even added: the borders between nations are today’s concentration camps, and though we see them, we turn our faces away. That too, he said, is one of today’s lies.)

Selim can map in a single sniff what I struggle to map at all: whom to approach, whom to push away, into whose ear to whisper. He is the type who senses the room instantly, who knows the network before it reveals itself. My father — and here pay attention — is not simply gullible. This is the trick. It is a collective falsehood. By handing over what he has, by paying the dealer or hiring Selim for the job, he is not just buying a car or a house (both of which fall apart). He is buying recognition. He buys a place in the visible order; he buys the nods, the street whisper, the confirmation that he belongs. Selim feeds him words as soon as he sees him (there’s a Turkish saying, ağzına göre vermek — to give according to the mouth), and the exchange is not transactional only in money. It is ritual: the money buys social currency, and through that currency my father receives something more than an object — he receives acknowledgment.

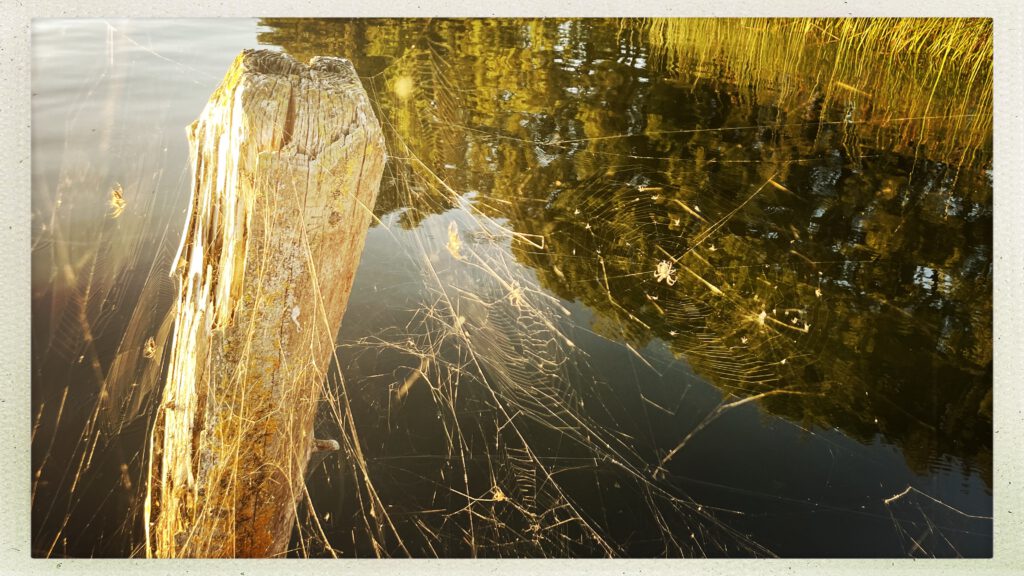

There is a Turkish proverb: even a whore needs an epithet. The point is blunt: whatever the underlying thing, what matters is the designation, the adjective, the presentation. It is never essence that counts, but how it is named, framed, articulated. And this, too, is the secret of Selim’s trick. My father was not fooled by what the car or the house was; he was caught by what it was called, the surface spun around it. In this sense, sociality itself is nothing but a weaving of epithets: like the hives of worker bees, the immense colonies of ants, the spider’s spinning web — all a fabric of attributes binding each to each.

My father had him do every job. Everything fell apart. Not even a month would pass before it collapsed. Yet my father, living in a village, had already succumbed to the idea of living in a villa, a whole meaning-world already spun by Selim. Just like those broken-down cars he kept buying.

(We all know in Turkey that car dealers are a kind of mafia. To buy from them is to be cheated — everybody knows this, and yet everybody still goes. The cheating is part of the scene. My father, by joining in, was not deceived; he was participating. By handing over his money, he was buying the recognition that comes with it, the glance on the street, the sentence in the air: “Look, he has a beautiful car.” And we all let it pass in silence. But when I broke the silence — when I named it for what it was — the rage that came back at me was the rage of the pact itself. That is why I say I was nearly crucified.)

I sometimes think religion itself may work like this. Not as belief in a transcendent truth, but as Spinoza once suggested, as a law to hold society together. A rule that is followed regardless of inner conviction, because its function is to stabilize the collective.

When they scold me — saying, “Be cool, don’t take things to heart” — they are not asking me to forget my troubles. They are teaching me a weapon: how to survive inside this order where truth is not what matters, but how it circulates. I remember as a child, there was a plant, a thin wild stalk with tiny V-shaped bristles, sharp as needles. Kids would play tricks by putting it in your mouth. The more you tried to pull it out, the deeper it burrowed. Truth and lies in this world are like that: the harder you try to separate them, the more entangled they become. Both pierce, both cling.

Because as time passes, I begin to realize that my family — often labeled conservative, even religious — may not actually believe in religion in any structural sense. They don’t live by doctrine; they inhabit the function. What is called religion here is less a system of faith than a fabric of rules, habits, words passed on. It works like the collective falsehood I have been describing: it doesn’t matter whether one believes or not, what matters is that the performance continues. The ritual of naming, of repeating, of nodding at the right moments — that is enough to keep the web intact.

And so, what is carried forward is not faith but form, not essence but articulation. The plant with its barbs is passed from one mouth to the next, not because anyone believes in it, but because the game itself sustains the community.

Now I am once again visiting my aunt. It always feels as if she is the only one who truly knows, sees, and accepts my fragile spirit. These days — perhaps also because of my illness — she shows me a special care, a tenderness that sets her apart. But my aunt is not only the one who consoles me; she also sits at the very heart of the vitek, the knot of family power. She embodies a symbolic authority: the hand that gives. Her generosity is not an afterthought but a constitutive force.

Even now, when everyone around her has become wealthy in their own right, she continues to distribute what is hers. She gives without hesitation, without calculation, and although materially she may be diminished, emotionally she grows larger. This is the paradox of her power: to lose in substance, but to gain in stature. To spend and yet accumulate. To diminish and yet expand.

In the universities, in the big cities, among the children of civil servants and educated families, my friends often dismiss everything as irrational. The support for Erdoğan, they say, is simply nonsensical. But they arrive at this judgment without ever defining what reason is, or asking how reason itself is lived.

My aunt, in her way, is sovereign under the law of giving. She distributes what she has, not to enrich herself but to preserve her symbolic power, her place at the center of the family map. In her hands, the gift diminishes her materially but enlarges her in spirit, in recognition.

The AKP, by contrast, politicized this same structure. They keep people in deprivation and then transform the act of giving into a staged miracle of power. But unlike my aunt, they discovered how to fold material profit into the circuit of bestowal. The government enriches itself while distributing crumbs. It is the same law, but with a trick: symbolic power fused with material accumulation.

From the perspective of Western education, of liberal reason, this all looks like backwardness, like irrational ignorance. But everything is in plain sight — only governed by a law these educated eyes refuse to read. They cannot see how in my neighborhoods, where people cannot even rise to the status of proper workers, inequality produces not just poverty but a dependence that masquerades as democracy.

I think of that line in the Batman film, when the Joker says there is so much inequality that sometimes people just want to watch the world burn. For those who live with nothing, nothing is ever lost; only the strange justice of seeing others lose, too. To watch the white-collar class tremble is, perhaps, the rarest form of pleasure they are afforded. This is something I might keep walking on it. but for now. Enough.

Each year I love to visit her in Mersin, especially in September, when the air feels like harvest. To see her in Antep is its own joy, but in Mersin it becomes ritual. Every year when I arrive, I rush to her with the familiar cheer: “My beautiful aunt!” Not because it is a simple truth — though she is beautiful — but because beauty here becomes a way of resisting change. Time passes, bodies grow frail, but in our words she grows stronger, more vibrant than last year. It is a collective lie, or perhaps a shared truth disguised as lie, that allows us to live. I tell myself I am lucky to carry her genes, to inherit what she embodies. Yes, we mostly lğie to ourselves as well. (Once, when my mother said, “We are all old now,” it pierced me like an arrow — my mother, my father, and I sitting together, already marked by time.)

With this cheer, the first act of sitting down together begins. A delicate balancing ritual. After a year away, I must recalibrate my own social map against the family’s. This is, quite simply, the function of gossip. Through gossip, last year’s truths and lies are reassigned, reshaped. I learn whether Nuray abla should now be inscribed in my map as a generous soul or as a schemer chasing hidden interests; whether my parents have become neglectful or whether they remain the only ones who gave everything for her; whether my little aunt, despite my Aunt’s support and labor, is cruel or caring in her distance. These calibrations are decided in the very first day’s gossip.

Here there is a delicate art. The first day’s balancing act is like a cat approaching an unfamiliar object. It sniffs from a distance, circles, tilts its head, even gives a sideways glance — and, if needed, makes a small, testing touch. I too learned to approach in this way, to begin by sniffing the air of the room.

I was not always able to do this. Once, my relations faltered because I could not perform this founding gesture of social life. I was left outside. Like the old Mongol practice of casting a child into the wild and refusing to take him back until he returned with a kill, I had to learn through trial. Survival meant training myself in this ritual: to sit at the table, to listen, to breathe in the atmosphere before I dared to speak.

My aunt begins by telling stories about someone — and always there is a helper beside her. In Mersin it is Havva abla; in Gaziantep, Serpil abla. Their voices fold into hers, like background instruments, reinforcing and complicating the melody of the tale.

I sit and listen as these dialogues are unfolded for me. A story is told: the umbrella left for months at the beach has broken, and my little aunt, angered by this, scolds my elder aunt. At first, this is only a scent in the air, a trace of relation. But it requires a sideways glance, a hesitation, because the data is not enough. From these first words alone, I cannot know whether my little aunt was right or wrong, whether her anger was just or misplaced.

So I wait for a second layer of data, a second eye. Havva abla’s voice enters: “Afterwards, her nose bled for days, from the sorrow.” Now the meaning shifts. From this I infer that my little aunt produced some kind of negativity. Yet even here the signal is blurred. Was it anger, was it sorrow, was it a deeper wound? I still do not know how to position myself.

Because Havva abla’s comment is not neutral. It emerges from her ability to read and interpret the balance of power, and from her own place within it. In that act of speaking, she transforms the relation as much as she describes it. But since I do not fully grasp where she stands in this web, or what founding forces shape her position, I cannot yet see how her map attaches to my aunt’s map. Without that knowledge, I cannot know how to read her words. They remain suspended — a clue without coordinates.

At this point, last year’s map begins to surface. I extend, like a cat, a small paw — a tentative touch. In my cartography, my little aunt has always been in part a daughter to my elder aunt. My elder aunt provides for her, keeps her under her economic wing. But the little aunt holds another role: she is the legislator, the one whose unwritten authority shapes the elder aunt’s world. The throne belongs to the elder aunt, but the vizier’s seat is occupied by the younger. She is the one who distributes power in practice. So strong, yet so fragile.

Because I have long read this bond as if it were a mother–daughter relation, I know how to make my move. I turn to my elder aunt and say: You are not strong now — you are ill, even though, mashallah, you still stand like stone. Your little sister was not angry that you broke the umbrella, but that you risked yourself in the act. She scolded you not for the thing, but for the danger of losing you.This small touch shifts the map.

From that small touch, the map begins to update itself. My aunt reveals the wound: not anger over a broken umbrella, but the bitterness of having been left alone. She tells me they abandoned her here, dropped her off and forgot her. The umbrella, the act of trying to lift it and snapping it in the process — these are trivial details, props in a larger play.

What truly happened was this: she felt deserted. And because the rules of our relations rarely allow truths to be spoken outright, she turned to allegory. She chose the umbrella, an object a month or two ago, lifted it in a moment of irritation, broke it, and then amplified the incident. A poet’s tactic. By dramatizing the small, she gave voice to the large, demanding that the web of relations be adjusted without naming the absence at its core. Even sultans, it seems, are caught in the networks they rule. No spider is ever free of its own web.